Last Updated on 11 February 2026

The Nigerian Senate on Tuesday reinstated mandatory electronic transmission of election results, reversing its earlier rejection following public pressure and criticism from civil society organisations.

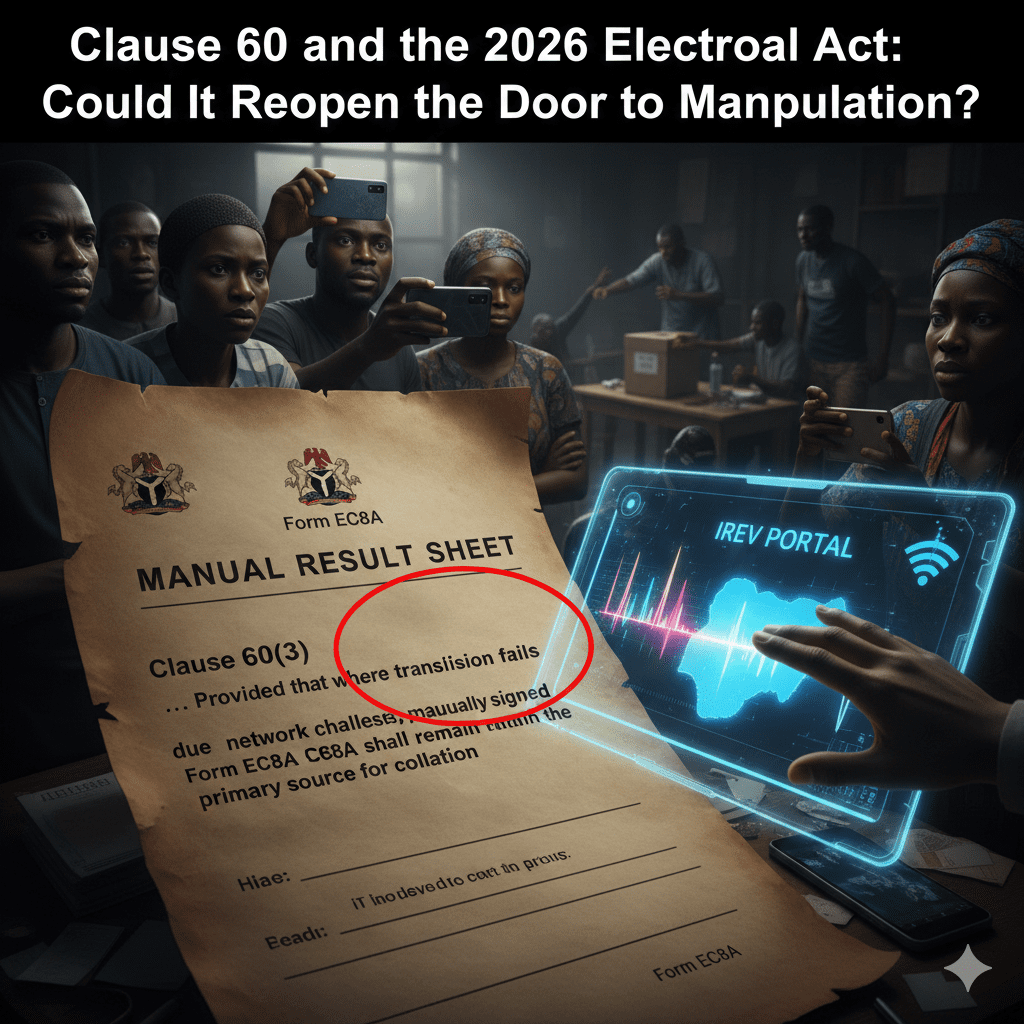

The amended Clause 60(3) of the 2026 Electoral Act states that results shall be transmitted electronically from each polling unit. However, it adds a proviso: where transmission fails due to network challenges, the manually signed Form EC8A will serve as the primary source for collation.

While civil society groups welcomed the move, legal analysts warn that the fallback clause could play a decisive role in how disputes are resolved during the 2027 general elections.

Transmission Failure and Manual Priority

Electronic transmission via the Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS) and publication on the INEC Result Viewing portal were central to recent transparency reforms.

The amendment retains electronic transmission but places the manual result sheet above the digital record if uploads fail. The operative phrase – “where transmission fails due to network challenges” – raises questions about verification.

Potential vulnerability: If transmission failures are not independently verified or logged transparently, disputed results could default to paper collation without real-time digital oversight.

INEC is expected to issue operational guidelines clarifying how such failures will be documented and audited.

Validity Without Party Agent Signatures

The framework also allows results to remain valid even if party agents are absent or refuse to sign.

Supporters say this prevents deliberate obstruction. However, past election disputes show that unsigned forms have often become sources of tribunal litigation.

Accountability concern: Where agents are absent or unwilling to sign, disputes may surface only after results are declared, shifting oversight from polling units to tribunals.

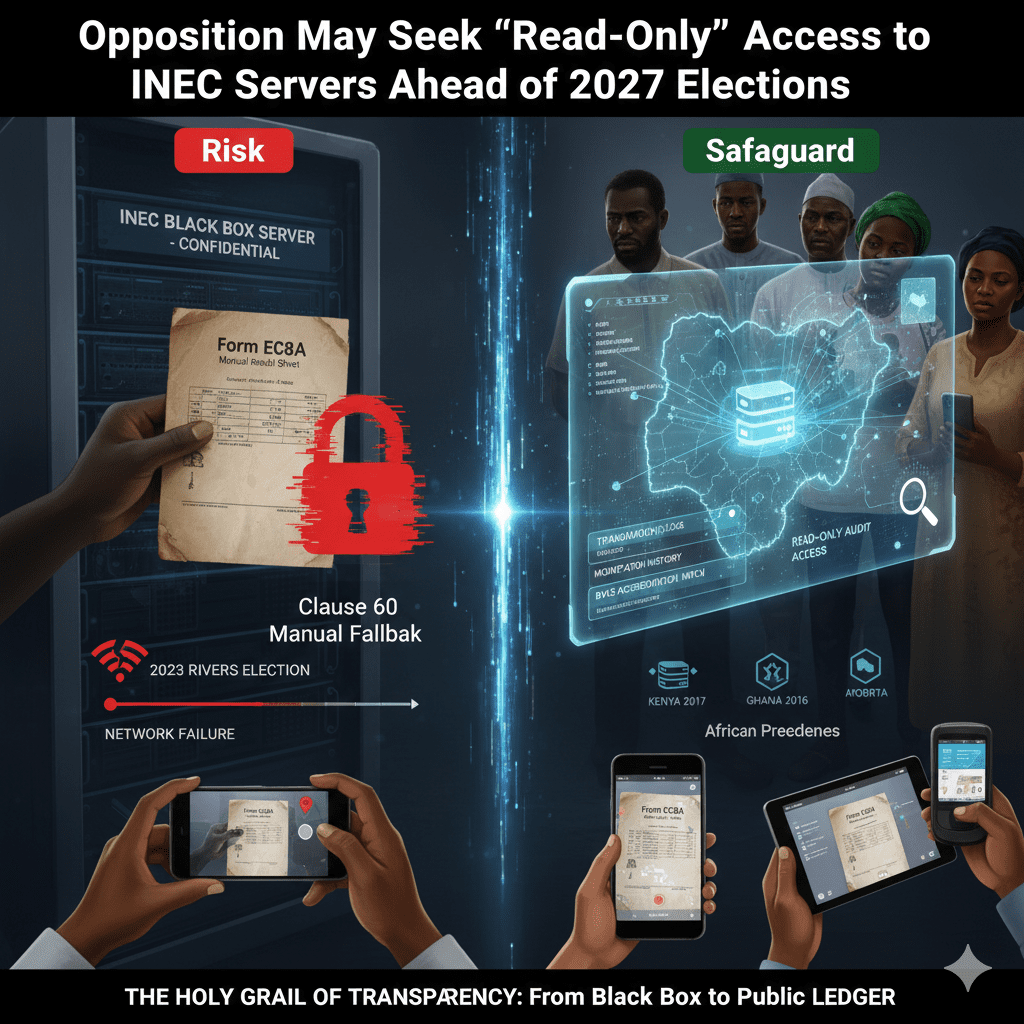

Internal Review Restricted to INEC

The law empowers INEC to review and correct falsified results, but only INEC officials may initiate such reviews. Political parties and observers cannot trigger administrative review directly.

Oversight limitation: If misconduct occurs at the official level, the absence of external activation mechanisms could delay corrective action until judicial proceedings.

NIN Requirement for Registration

The amendment introduces a requirement that prospective voters possess a National Identification Number (NIN) before registration.

Authorities argue that this will strengthen the integrity of the voter register. Advocacy groups caution that delays in NIN enrolment, particularly among young voters and in underserved regions, could affect participation.

Administrative risk: Bottlenecks in NIN issuance could indirectly limit voter registration in certain areas.

Shorter Notice Period and Higher Spending Cap

The revised law reduces the election notice period from 360 days to 180 days and raises the presidential campaign spending ceiling to ₦10 billion.

Analysts say the compressed timeline may favour established parties with existing structures, while the higher spending cap could advantage well-funded incumbents over emerging candidates.

Competitive imbalance concern: Shorter preparation windows and increased spending limits may reduce opportunities for smaller or grassroots campaigns to compete effectively.

Implementation Remains Key

Civil society groups have welcomed the Senate’s reinstatement of electronic transmission but emphasised the need for detailed procedural safeguards.

As preparations for the 2027 elections begin, attention is shifting to how INEC defines, records, and communicates transmission failures and enforces internal review mechanisms. The credibility of the 2026 Electoral Act may ultimately depend less on statutory wording and more on the integrity of its implementation.